Tribal Story

Pre-Contact

Pre-Contact Traditional Way of Life

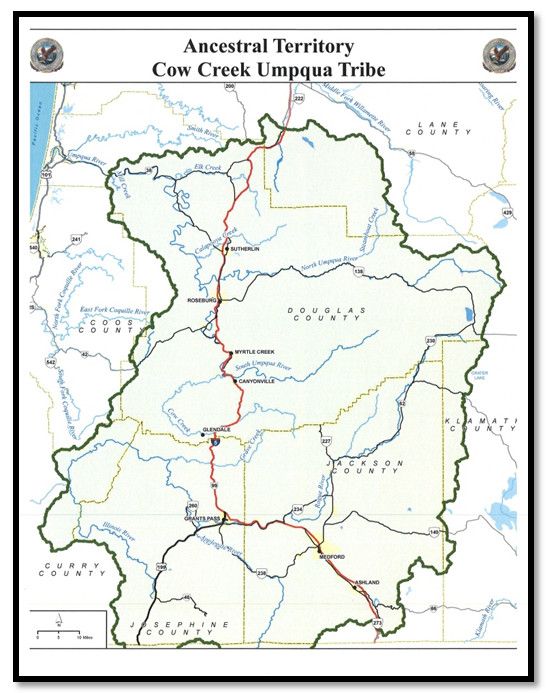

For generations, our people, the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians, lived between the Cascade and the Coast ranges in the Umpqua and Rogue River watersheds in southwestern Oregon. Our homeland was one of high mountains, forested uplands and valley floors that provided abundant resources to sustain our tribal way of life. The heart of our country was concentrated on the South Umpqua River and its primary tributary, Cow Creek.

Along the glistening rivers and streams, salmon was harvested using various methods of capture including spearing, netting, and trapping. Stick dams were constructed across creeks and funnel-shaped baskets made of hazel shoots were placed in narrow channels to catch salmon as they surged upstream. Men also plunged into the water to tear large numbers of lamprey from the rocks. Both salmon and lamprey were smoked and dried, serving as stored food used during the winter months. Creeks and rivers provided additional nourishment in the form of trout, crawfish and freshwater mussels.

Along the glistening rivers and streams, salmon was harvested using various methods of capture including spearing, netting, and trapping. Stick dams were constructed across creeks and funnel-shaped baskets made of hazel shoots were placed in narrow channels to catch salmon as they surged upstream. Men also plunged into the water to tear large numbers of lamprey from the rocks. Both salmon and lamprey were smoked and dried, serving as stored food used during the winter months. Creeks and rivers provided additional nourishment in the form of trout, crawfish and freshwater mussels.

Deer, elk, and bear were plentiful in this region and were secured using several techniques. One traditional method of hunting was the communal game drive. This involved construction of long brush fences across heads of canyons and forcing deer to pass through a narrow place where men had fixed iris fiber snares. Traditional bow hunters would also stalk their prey wearing a dried deer-head decoy. Every part of the animal would be utilized. Meat was dried, hide was tanned for clothing, bones were made into tools, dewclaws were used for rattles, and sinews were used as bow string. Bear was particularly prized for its grease and marrow, and its claws were used as ornaments.

Our ancestors also gathered ample seeds, nuts, and berries. Acorns were collected, ground, and prepared for winter storage. Collecting tarweed seeds was a two-part process of burning fields to clear away the plant’s sticky substance, then beating the tarweed pods over a basket to harvest the seeds. Tribal women would gather vast quantities of camas bulbs by using deer horn-handled digging sticks and tossing the bulbs over their shoulder into burden baskets. After baking in an earth oven, camas bulbs could be sun-dried or mashed and formed into cakes that could be stored for winter use. Other essential plant foods included hazel nuts, chinquapin, elderberries, blackberries, strawberries, service berries, salal and blackcaps.

A significant social and food-gathering activity for our Tribe came in late summer and early fall, when families moved far up to the Rogue-Umpqua Divide. Here, we picked huckleberries and dried them in the sun on large flat boulders. At night, under the stars, we sang songs and told stories that had been handed down generation after generation.

When nights began to chill and the prospect of winter rain set in, our people dropped down from the mountains, abandoned the temporary huts of limbs and reed matting and took up residence in the permanent winter villages in the lowlands. The villages consisted of several plank-houses: semi-subterranean lodges constructed of split wood planks set on four upright posts. Four cross-beams supported the roof and were lashed to the corner posts and ridgepoles by hazel bark cordage. A notched log served as a ladder that provided steps down to a main activity area around a central fire pit. These dwellings also housed the gathered foods such as acorns, hazelnuts, cakes of camas, tarweed seeds, smoked salmon, lamprey, and dried meat.

Life continued on in this way for our Tribe until contact with Euro-American newcomers in the early 1800s.